Use it or lose it. It’s a saying that applies to any skill, and it appears that federal trademark courts also believe in it, or so says attorney John Welch of Cambridge, Mass.-based Lowrie, Lando & Anastasi LLP in his TTABlog.

Use it or lose it. It’s a saying that applies to any skill, and it appears that federal trademark courts also believe in it, or so says attorney John Welch of Cambridge, Mass.-based Lowrie, Lando & Anastasi LLP in his TTABlog.

Please read the post. It talks about the case of General Motors Corp. v. Aristide & Co., Antiquaire de Marque. The case is about a French company named Aristede, which is in the business of registering old trademarks and selling them. It registered the car brand LaSalle. General Motors was upset, and opposed the registration. Aristede won.

This is fascinating news. For a very long time, intellectual property departments at companies have been trying to have it both ways. They want others not to be able to use the trademarks of products they have abandoned, citing the fact that there might be confusion in the minds of the customers. Yet they do absolutely nothing meaningful to actually keep the brand alive, save some sort of lame licensing program. One precedent we find fascinating? The Humble case, where a startup company registered the name Humble and Exxon proved that the residual connection would confuse consumers.

In one sense, this will be good for both the consumers who like old brands, and the companies that produce discontinued products. If there is equity in an old brand, the company will have to come up with MEANINGFUL ways to use the brand name.

What would be precedents here? Please look at our BrandlandUSA list of 100 brands to bring back. GM Brands like Fisher Body and Plymouth are on the list, and need to be used to be protected. Here are some others:

- LaSalle Bank. Bank of America discontinued the brand, and when you go to the LaSalle website, it goes to Bank of America.

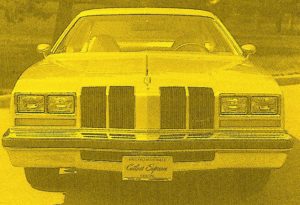

- Oldsmobile. GM discontinued the brand. While it claims the brand on its website, and certainly (we hope!) allows some licensed materials related to Oldsmobile (toy cars, logo shirts, etc.), it needs to actually produce something like an Oldsmobile-branded car to keep the trademark REALLY alive.

- Burger Chef. Apparently Hardee’s produces the occasional product from Burger Chef, and had registered the trademark.

- Amoco. BP needs to keep using the Amoco logo to keep its trademark protection. Currently it is in a diminished spot on BP pumps.

- Marshall Field. Macy’s has dozens of regional department store brands, including this notable one. Brands like Burdine’s, Abraham & Straus and Thalhimers have been discontinued. If these brands are not USED in a meaningful way, they can be abandoned. What is to stop a family member from opening a store with the old name if it is not used?

So what should you do if you, the company with old brands that have been discontinued? Here are some thoughts:

- Produce some commemorative products that are meaningful, on a fairly regular basis.

- Meet with a brand licensing firm to establish new uses for an old brand. Companies like David Milch’s Perpetual Licensing are possibilities. There are many of these firms out there.

- Consult with a good intellectual property law firm to devise MEANINGFUL ways of protecting the brand in court.

- Sell the brand to another company.

- License the production of the product to another company. This is what Proctor & Gamble does with Noxzema Men’s Shaving Cream.

- Work with consumer fan clubs to harness the equity connected with the company in case there is a future use for the name. For instance, if you make parts for a discontinued brand, put the name of the brand on the product.

- Have a vigorous licensing program for the logos. So theoretically, if Boeing isn’t able to produce a Douglas Aircraft, it can at least protect the logo design.

If I understand Welch’s point properly, he refers to the issue that Aristede had not actually made the LaSalle car when it filed. This means that there is not only a burden on a company to produce the product to keep the brand alive. It also means that trademark companies CANNOT “trademark squat”, and register all sorts of old names in the manner that people buy and squat on URLs.

An excerpt from the decision: We conclude that opposer’s LASALLE mark was abandoned for a period of at least three years after 1940. Opposer has neither shown that it had an intent to resume use nor established a subsequent priority date. Therefore, opposer cannot prevail in this opposition because it has not established a date of priority before applicant’s priority date.