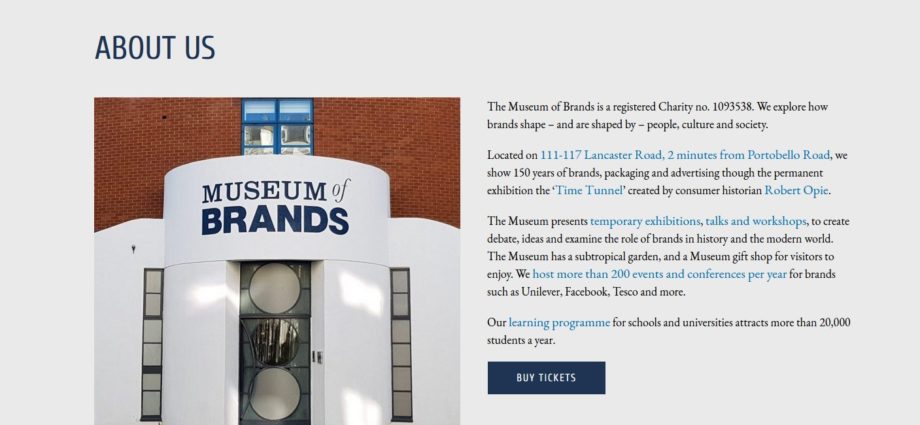

NOTTING HILL – Those visiting the famed Portobello Road market in London ought to take time and visit the nearby Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising. This museum tells the story of brand names in the U.K. with a collection of half a million items, including candy, appliances, food and fashions.

NOTTING HILL – Those visiting the famed Portobello Road market in London ought to take time and visit the nearby Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising. This museum tells the story of brand names in the U.K. with a collection of half a million items, including candy, appliances, food and fashions.

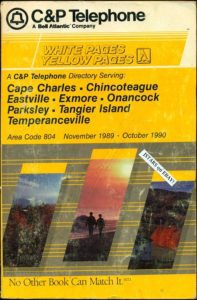

The museum is laid out by decade; 10,000 of the items are shown. The museum cites not only its consumer product collection, but its collection of technology, as brands are one of the easiest ways to teach the history. Items include an 1895 Gower-Bell telephone, a 1911 Star Vacuum Cleaner, an 1890 Rippingille oil warming stove and the world’s first portable gramophone, the 1909 Pigmy Grand.

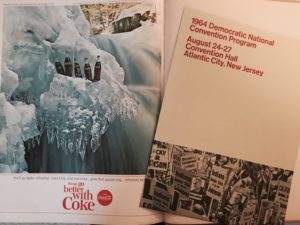

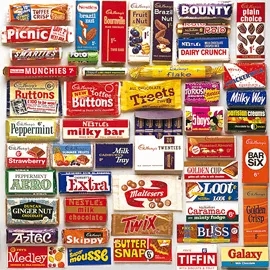

Currently, the museum is showing Biscuit Bonanza, which details the history of biscuits in the U.K., and Sweet Sixties (image at right), which tells the story of candy in the 1960s. Fun stuff.

Founder Robert Opie calls all this branded packaging evidence of a “dynamic commercial system.” We agree.

The museum was founded when Opie started collecting packaging in the 1960s. The collection grew, and grew. It was first housed in the Museum of Advertising and Packaging in Gloucester but moved to London in December 2005. It is led by Chris Griffin; the collection is a registered charity but it was rescued with the effort of the agency PI Global, with whom it shares space.

The board is a sort of brand name all-star list, including Peter Blackburn, Lord Briggs, Sir Dominic Cadbury, Lord Chadlington, Niall FitzGerald KBE, Professor Sir Christopher Frayling, Baroness Greengross, Lord Heseltine, Lord Hollick, Lord MacLaurin, Robert Opie, Lord Sainsbury of Preston Candover, Sir Martin Sorrell, Galen Weston, Sir Robert Worcester. The chairman is Sir Paul Judge, and chief executive, Chris Griffin.

Below is a quote from Opie:

On 8 September 1963, at the age of sixteen, I bought a packet of Munchies at Inverness Railway Station. While eating them I was struck by the idea that I should save the packaging and start collecting the designed and branded packages which would otherwise surely disappear forever. Forty years later, I am still collecting and have a list of about 1,000 items which need to be collected. The Museum houses the highlights of my collection – evidence of a dynamic commercial system that delivers thousands of desirable items from all corners of the world, a feat arguably more complex than sending man to the Moon, but one still taken for granted.

The collection has the power to stop visitors in their tracks as they reach a certain part of the Museum’s time tunnel and the era which contains their first memories. This could be provoked by a can of Quattro, Texan bar, Kodak camera, children’s comic, 1950s jukebox, baked bean tin, packet of tea or bar of soap. Each object has its own significance for every person who enters the Museum.’