This Christmas, thousands of American families will pull out their Lenox Holiday china, ensuring that their 2020 family dinner will be just as it was last year, and the year before, and the year before. Roast beef, ham, turkey and other things, will sit smack dab in the midst of a gold-banded white plate, ringed with holly and berry. While thousands of other patterns come out of sideboards and breakfronts at this time of year, the gold framed circles of Lenox Holiday are one of the best-known patterns of the Lenox China company, which this year ceased making china in the U.S.

This Christmas, thousands of American families will pull out their Lenox Holiday china, ensuring that their 2020 family dinner will be just as it was last year, and the year before, and the year before. Roast beef, ham, turkey and other things, will sit smack dab in the midst of a gold-banded white plate, ringed with holly and berry. While thousands of other patterns come out of sideboards and breakfronts at this time of year, the gold framed circles of Lenox Holiday are one of the best-known patterns of the Lenox China company, which this year ceased making china in the U.S.

Some will consider fine china a hopelessly antique idea. Many think china is too precious, and so it is never used. Others prefer heavy, peasant-style pottery and crockery. Others still use the china, but only once a year, which makes it a bit precious. The reality is that a good set of china can make any meal memorable; in a time when a Doordash order is $100, even the most expensive bone china is cheap.

Founded in 1889, by Walter Scott Lenox, Lenox China was and still is in some places the emblem of Americanism at the American dinner table. In wealthy houses, brands like Wedgwood and Limoges were, and are, still popular. German brands like Rosenthal were and are sort of flashy and mid-century modern. But Lenox had a sort of different standard for most upper middle class wedding sets after World War II. It was American. Not Americana, but American. And it gained particular status in the 1950s and 60s, when its simple colors, straightforward patterns, and gold bands redefined, and simplified, what a formal dinner table looked like.

Through history, much of fine bone china was (and is) often covered with patterns, and color. Lenox, while it had plenty of patterns, kept the decoration to a minimum. Patterns like Hayworth, Westchester, Hayworth and Montclair were all obsessively straightforward. The food came first; the plate was a stage. This image was helped by its “by appointment” status to the White House, where Lenox provided successive administrations their White House china, beginning with Woodrow Wilson. The most famous in recent years was the Reagan china. (Michelle Obama, however, had White House china produced by Pickard China of Illinois.)

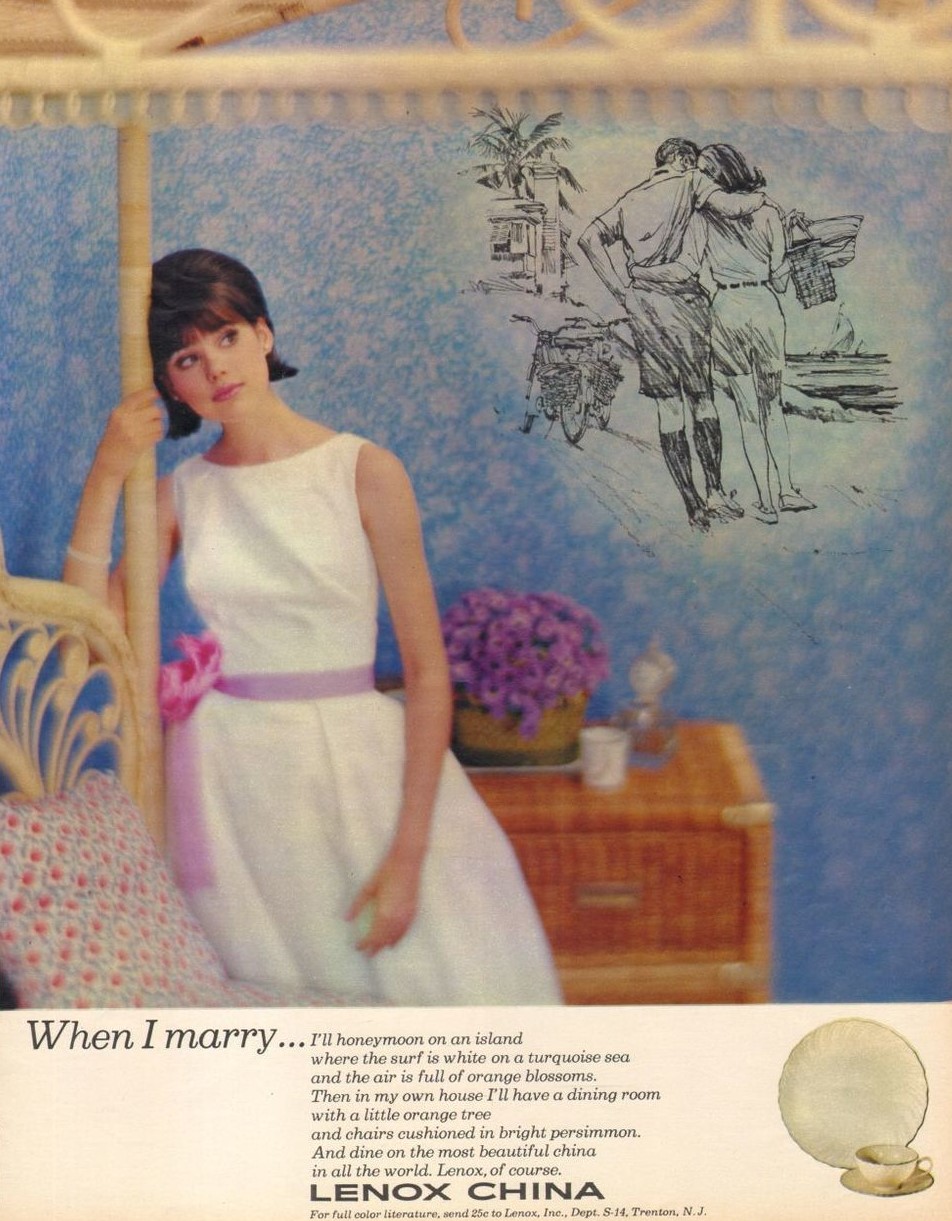

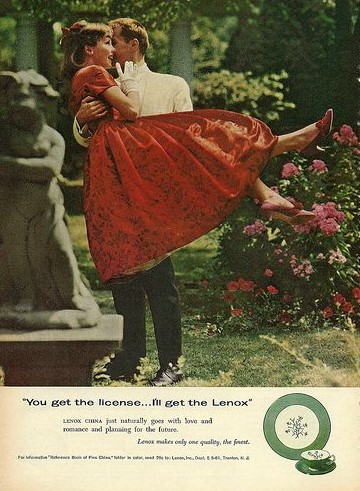

Lenox’s image was helped in image making through some of the nation’s largest and most storied advertising agencies, beginning with national campaigns with Benton & Bowles in 1950, and later with D’Arcy. Bone china, like sterling silver, was once seen as an essential part of a household; the ads reinforced the connection.The ads, seen below, said, “You get the license. I’ll get the Lenox.” The ad then ended with, “Lenox only makes quality, the finest.”

The story of comedienne Joan Rivers is instructive in this regard, even though she was not known for her Lenox tabletops. Rivers was renowned for her entertaining and formality, and she often told the story of her mother, who insisted on a formally set table, in spite of their limited means, while living in a tiny apartment in New York. The reason? They had come from means, in another era in Europe, and they were upholding standards, for a future time, when they would again.

A Christie’s story about her collection, “Memories of Joan Rivers the Hostess”, tells the perspective from columnist Suzy, aka Aileen Mehle:

Joan was a fine hostess because she was always full of fun and laughter. She loved to entertain. She gave a Thanksgiving dinner every year for all her closest friends and always set the table beautifully; she had such wonderful silver and china.

Bankrupt and Reorganized

The company had a number of owners that did not understand it, beginning with Brown-Forman, the Kentucky distillers, and Department 56, a trinket collectibles company. (The latter certainly did not meet the “only one quality” statement.) In 2008, the company filed for Chapter 11, in order to reorganize. In April 2020, the company closed their Kinston, N.C. factory, saying that they would be off-sourcing that production to Asia and Europe. This fall, the company announced a sale to the New York venture capital firm Centre Lane Partners. Today, the future is a question, though the brand will survive as a licensing play, certainly.

The company had a number of owners that did not understand it, beginning with Brown-Forman, the Kentucky distillers, and Department 56, a trinket collectibles company. (The latter certainly did not meet the “only one quality” statement.) In 2008, the company filed for Chapter 11, in order to reorganize. In April 2020, the company closed their Kinston, N.C. factory, saying that they would be off-sourcing that production to Asia and Europe. This fall, the company announced a sale to the New York venture capital firm Centre Lane Partners. Today, the future is a question, though the brand will survive as a licensing play, certainly.

It is a great brand. The company includes Reed & Barton Silver, itself a treasure. Sadly, earlier versions of the company ruined historic silver brands like Kirk Stieff Company and Gorham, and ventured into lower categories of housewares, including a melamine line.

The company archives are in public hands at Rutgers, so the history will not be lost. Their china collection and related museum pieces formerly held by Lenox, Incorporated, were donated by Brown-Forman to the Newark Museum and the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton. And the actual plates owned by customers? They will survive for generations, in households, and at antiques stores. The question is how the company will operate going forward, as it is no longer making products in the United States, which was essential to the American brand promise of Lenox.

U.S. New to China

When Lenox came to the White house in the early 20th Century, the United States had not had makers of fine bone china; the most desirable brands, since the 18th century, had been English, French and perhaps German.

In recent decades a number of trends had made the bone china business difficult, and these were trends not all of their making. These factors included department store consolidation, the closure of regional jewelry and accessories stores, and changes in entertaining styles. Even the decline in traditional marriage since the 1960s has hurt Lenox; with fewer weddings, and smaller families, the market contracted. The disappearance of the dining room also hurt the idea of fine dining; a barn table in a giant barracks kitchen will do, according to our Fixer Upper friends in Texas.

Their spring press release on the closing said that that their 218,000-square-foot Kinston factory was built in 1989. “The factory was renowned in the industry for its “innovative and unique manufacturing capabilities”, including hand-enameled dots, etching techniques and microwave-safe metals. The Kinston plant produced nine of Lenox‘s top ten patterns and could produce 15,000 to 20,000 pieces of fine china daily.” A stunning loss.

Their CEO, Mads Ryder, said at the time that with “130 years of business behind them Lenox will continue to remain strong and its heritage patterns will continue to be designed and developed in the U.S. and manufactured in Europe and Asia.”

Translate? We will offshore, try to keep our nice office staff and corporate operation, and think we can make it as a licensing company. “It has been a very difficult decision to decide to close the factory. It is closing a chapter in Lenox’s long and illustrious history as an American manufacturer of fine dinnerware products,” said Ryder, in a press release. “These achievements were only made possible by the competent, dedicated and proud team of the Kinston factory.”

What should the route going forward be?

- First, there must be some bone china made in the U.S. Perhaps the company runs a smaller craft studio operation that produces high end plates, and other sub-brands and lines can be made outside the country?

- Secondly, they need to have some sort of operation in Trenton, where they were born. They ought to work with the Potteries of Trenton Society to help reinvigorate a pottery industry in New Jersey. I am sure Gov. Phil Murphy would get this sort of project rolling. Call the pattern Drumthwacket, after the state executive mansion in Trenton, and entertain liberally once the virus is gone.

- Lastly, they need to end the fashion lines. Dinnerware, while adhering to some sort of good taste, is not at all about fashion. It is about buying something expensive that will last for generations.

This could be good time for Lenox, and all things American. When the virus goes, people will want to have the family over for a large dinner. And in a time when we spend $1,000 for caterers or supplies for a dinner, why not spend the same amount for something decent, and not Pottery Barn, to serve it on.

The New York company Sherill Manufacturing, founded in 2005, now makes stainless steel flatware at a plant in Sherrill, New York, and is the only U.S. manufacturer left in that sphere. Across the country, small startups are reviving local manufacturing, amid a demand for American made objects.

In the meantime, enjoy this history of White House china from the 2016 National Book Festival. White House curator William Allman presents “Official White House China: From the 18th to the 21st Centuries” and “The White House: Its Historic Furnishings and First Families” below. The history detailed shows the history of the collection, and the beginning of the collection from James Monroe’s administration onward.

The history will convince of the importance of this work, and the need for a future for the industry:

Sadly a gift my daughter gave me of a Lenox travel mug broke and I wanted to replace it. How mortified was I to discover that it no longer said American by Design. I turned over the new one only to discover on the box (not the travel mug itself) that it was made in China!

I thought it was a mistake, but once I Googled it discovered that it was not. The design is the dance, but the finish is different and so are the colors! I’m so sad