“Buy only the best pencils. The others are a snare, a delusion and utterly useless.” -Eberhard Faber II

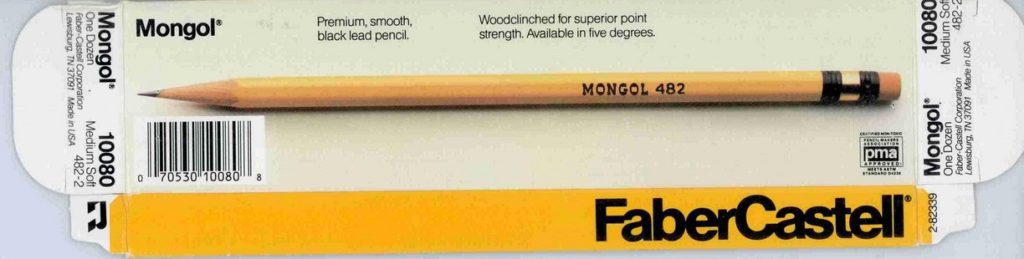

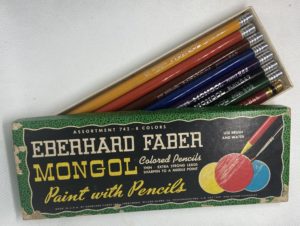

The book Quintessence, published in 1983, profiled a series of American products that were perfect, and could not be improved. One of those brands, along with Coca-Cola, Slinky, Oreo and the Cartier Tank Watch, was the perfect Eberhard Faber Mongol #2 pencil. Authors Betty Cornfeld and Owen Edwards, in their Crown Publishers Book, wrote that to write with anything other than the Mongol #2 482 was to “hamper your creativity.”

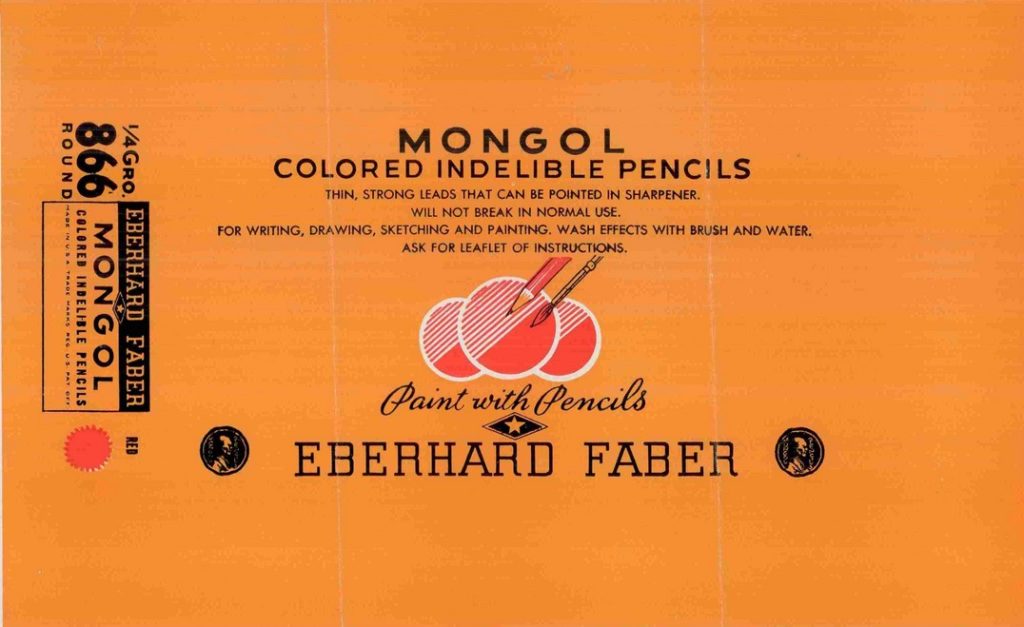

Cornfeld and Edwards cited a number of important features about the Eberhard Faber Mongol, including the fact that the #2 was dipped 13 times in yellow paint, and had been made at one time at the waterfront East River site of the United Nations. The Mongol name, they surmised came from either the country, or a yellow type of Indian soup. A Rotarian article wrote that it was because the graphite was a special product of Siberia and Mongolia.

A later interview with Eberhard Faber IV said it was decidedly the soup.

“John Eberhard, who was my grandfather’s brother, and as head of sales, founded the United States Trademark Association. He did it to protect the Mongol trademark, which was one of the original trademarks in the trademark association. He was also responsible for naming the Mongol pencil, which was named after—not the Siberian graphite which he is often given credit for—but after his favorite soup: Purée Mongole.

Contrapuntalism.blog

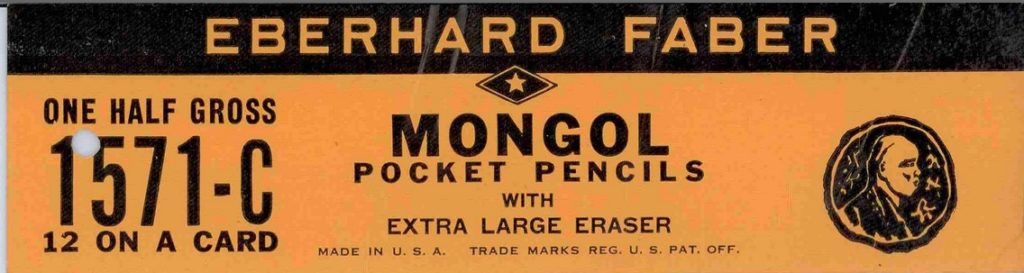

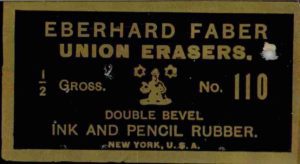

The interview with Faber IV also has another little nugget. Apparently the United States Trademark Association was founded in part by Eberhard Faber, in order to protect the fame of the popular Mongol pencil. The Mongol was officially trademarked in in 1949, though the product gives a first use as the nondescript date “0-00-1900” which means that it has been a part of American landscape since the 19th Century. Many different dates have been surmised.

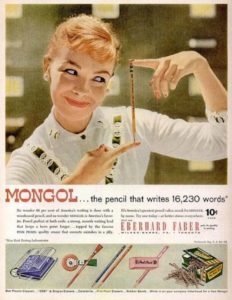

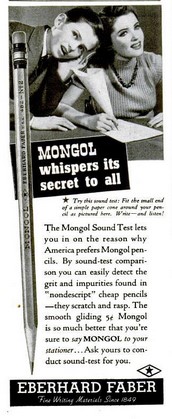

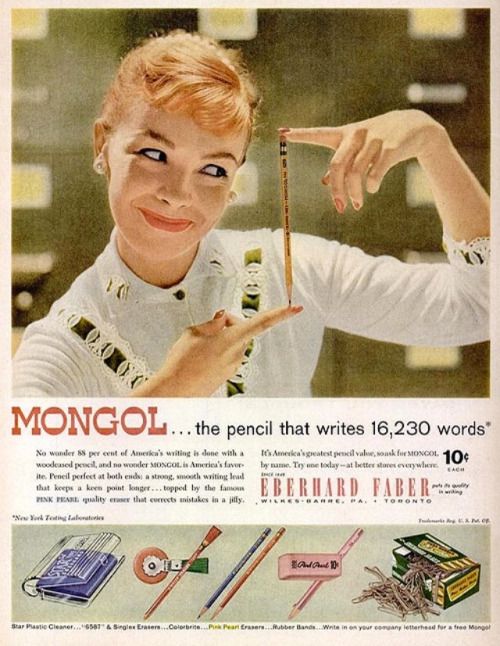

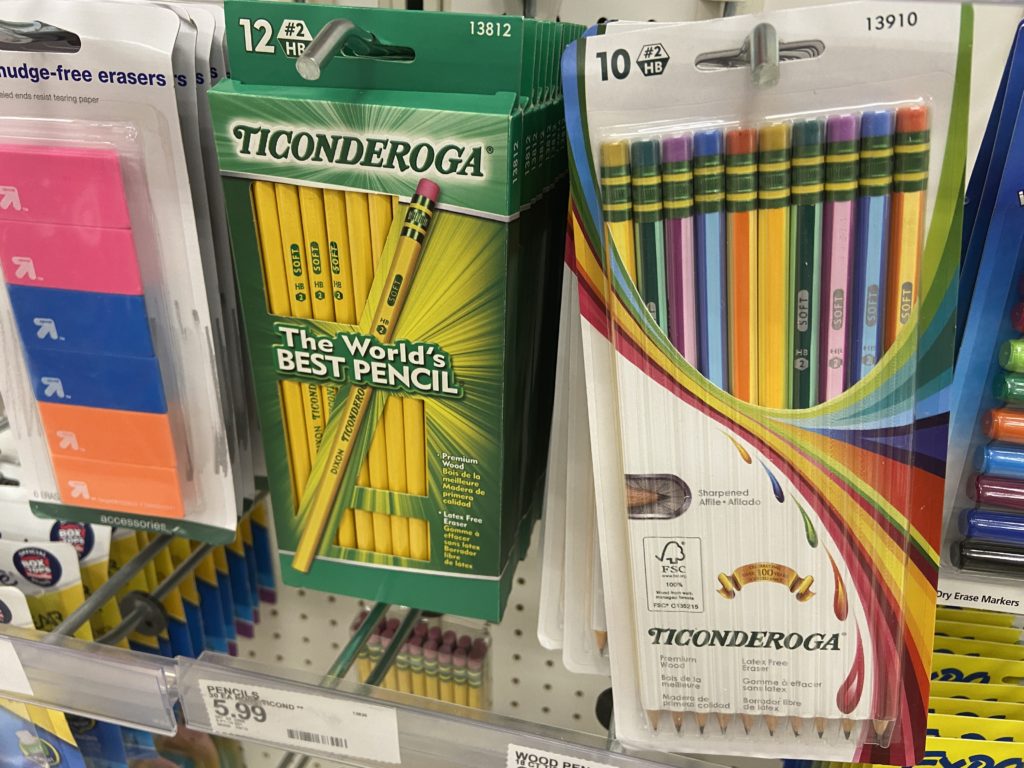

Advertising in the 1950s said that “America’s Favorite Pencil” would write a stunning 16,250 words, a fact found thanks to a Yesteryear Ads on Tumblr and Cory Doctorow. The company sold many variations on the pencil, including including color sets, seen at top, and an XMAS pencil, which had green and red as the lead.

Owens and Cornfeld’s book should be mandatory reading for any brand manager, or anyone interested in how brand value is conserved. Of the Mongol, they also attributed the whole idea of pencil yellow to Eberhard Faber. And where would life be without that? The other part that they valued about the Mongol was the quality of the erasers, and the fact that the original Mongol could be sharpened 17 times.

The shade of yellow is so famous that the shade is sometimes called Mongol yellow, a phrase used by the Catholic Priest of the Philippines, the Rev. James B. Reuter. The pencil itself is so famous that hundreds and hundreds of books and magazines refer to the Mongol pencil by name. Artist Chuck Close used them, along with many others.

Faber Castell and Eberhard Faber

Newell Brands now owns the trademark to the Eberhard Faber pencil brand in the United States, often confused with the German Faber-Castell, a separate company. There is also an overseas Eberhard Faber site. The families were/are related, and there is some confusion as Newell Brands purchased FaberCastell in the U.S., then sold it. The Mongol was once sold as a FaberCastell product.

Newel/Sanford also is the last listed owner of the Mongol trademark, through subsidiary Sanford LP. The trademark is up for renewal, and appears to be past deadline. The valuable Eberhard Faber brand, which lists first use as 1861, was renewed by Newell in 2018.

The Faber-Castell brand in the U.S. is owned by “Faber-Castell Aktiengesellschaft Corp., Federal Republic of Germany, Nurnberger Strasse 2 Stein, 90546.”

The unfortunate part of the disappearance of the American made products of Eberhard Faber is that they once made dozens of different pencil brands, with different woods, metals and leads, meaning that a whole American writing vocabulary and language has been lost. A whole machine tool and production vocabulary has disappeared. That’s not to mention the hundreds of jobs and taxes, and the farms and shipping it employed.

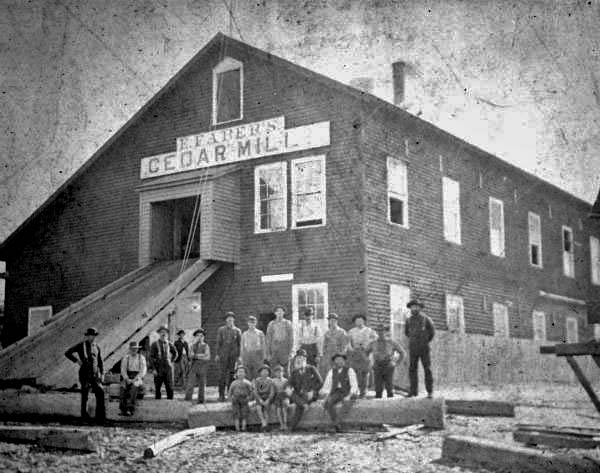

The Cedar Key area of Florida is connected to Eberhard Faber. It was there that he found the splinter-free wood needed to make pencils, and purchased much of the land. There is a Florida history marker mentioning the role played in economic development there, and the mill on Atsena Otie, or Depot Key. The company had a mill where it processed the cedar, owned by the company.

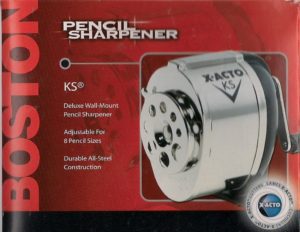

Today, the pencil is seemingly generic, and most would not even pay attention or care that a pencil was a #2 or #1 grade. But in its heyday, the models of Faber pencils included Monitor, Van Dyke, Principal, Tiger, Weatherproof and Elementary. Those of a certain age will remember that small children were given large pencils in early grades. Also missing as part of the discussion is the actual sharpening of pencils. The Boston KS sharpener, seen in most classrooms and profiled on BrandlandUSA.com, could accommodate many different sizes of pencil. Cheap plastic desk sharpeners cannot.

The Mongol pencil has made many cameo appearances. John Steinbeck is said to have used three pencils, the Mongol, the Blaisdell Calculator, and the Eberhard Faber Blackwing when writing his novels. It took 300 pencils for The Grapes of Wrath. Note that a story on the pencils shows a Mongol 480, not a 482. Apparently these are small but important differences to collectors.

The Mongol 482 #2 pencil was also used as a demonstration of economics by Milton Friedman in his libertarian documentary, Free to Choose. The pencil was used as a example of the usefulness of pure capitalism. It was one such product that would be impossible without thousands of intricate trading relationships and the economies of scale of factory production.

Said Friedman of the pencil:

I haven’t the slightest idea where it came from. Or the yellow paint! Or the paint that made the black lines. Or the glue that holds it together. Literally thousands of people co-operated to make this pencil. People who don’t speak the same language, who practice different religions, who might hate one another if they ever met! When you go down to the store and buy this pencil, you are in effect trading a few minutes of your time for a few seconds of the time of all those thousands of people.

Milton Friedman, Free to Choose

The Mongol 482, and other pencils were later sold under the FaberCastell brand (see below), and made in Lewisburg, Tenn., where the Eberhard Faber factory moved in the late 1950s. Even more confusing. There are still pencils made in Lewisburg, at the J.R. Moon factory.

Newell Rubbermaid and Sanford renewed the Mongol trademark in 2009.

They were apparently made in Venezuela as late as 2014, but those supplies have dried up. The Gentleman Stationer blogger found the Mongol under the Paper Mate brand, but they were round, and not sided, which means that they roll on a desk. They have since disappeared. The closest item is the Paper Mate Ever Strong #2 pencil, sold at stores across the U.S. There is artwork related to the Eberhard Mongol on a Colombia twitter page, but the last post is from 2016.

Newell has yet to respond to the USPTO over whether they will renew the Mongol brand. It would be a great loss to American history to have that product expire.

Below, a gallery of items relating to the Eberhard Faber Mongol. Below that, the Dade Scolari Weekly Pencil Instagram.

Mongol pencils in the Philippines are still the country’s best-selling pencils with millions of users annually. Although it’s in a market share battle against other brands especially those made in China, it maintains leadership due to nostalgia and strong brand affinity and loyalty. When you need a pencil in the Philippines, it must be Mongol Pencil 482, especially during admission tests or licensure examinations or at schools and universities.

Mongol pencils were revived by a company in the Philippines, matching all the original specifications. I have used them and can say, they are as good, and the erasers are better, as they are not containing grains that will scratch the paper, and seem to get softer with use, and do not dry out.

My favorite pencil, however, was the Pedigree no. 2, which had a blacker line, a green eraser that was softer, but still held its point. I suspect Mongol has a little more clay in the lead and that’s why it stays sharp longer, which is why it was the standard pencil for editors to use.

There’s a lot more to the story of pencils. As for confusing brand-name history, look at Butter-Nut Coffee, which is being revived in Alpharetta, Georgia.