New York – On March 16, the board of the National Audubon Society announced that it had decided to retain the name of the organization, after a lengthy process to examine its name in light of the “personal history” of its namesake John James Audubon. The organization said that the decision was made “taking into consideration many factors, including the complexity of John James Audubon’s legacy and how the decision would impact NAS’s mission to protect birds and the places they need long into the future.”

“After careful consideration, the Board elected to retain our name,” said Susan Bell, Chair of the National Audubon Society’s board. “The name has come to represent so much more than the work of one person, but a broader love of birds and nature, and a non-partisan approach to conservation.”

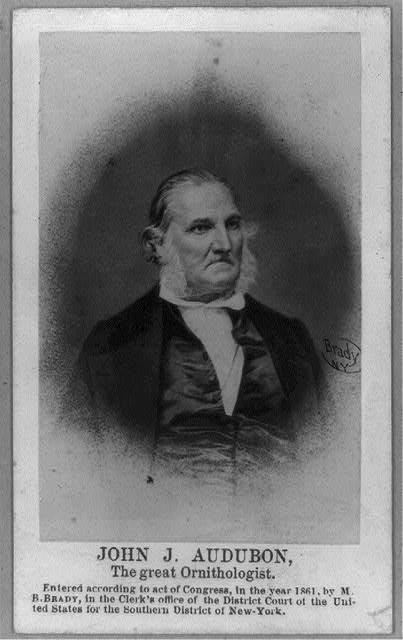

The decision to keep the name was a strong, commonsense move, and a realization that John James Audubon not only invented the idea of bird conservation, but created an infrastructure and intellectual system that enabled the conservation of one of God’s most beautiful and noble creatures. Like early naturalists John Bertram and Mark Catesby, Audubon studied not only the birds themselves, but their habitats. At the time, there was no idea or appreciation for the finite aspects of wildlife, and Audubon deemed the birds worthy for their beauty, and not as hat plumage, or dinner. A key part of Audubon’s effectiveness was that he was part of the leading social classes of the United States at the time, a society that still had not abolished slavery.

Society Created Early 1900s

The founding of the National Audubon Society came in 1905 after the life of Audubon, in the wake of the use of rare birds for women’s hats. Numerous state Audubon Societies gathered together in a national organization. The groups had helped create the first National Wildlife refuge, Pelican Island, in Florida, in 1903. Efforts like the annual Christmas Bird Count evolved as a way to note the nation’s bird popuation.

A curator tour from the Bell Museum in Minnesota tells a bit of Audubon’s life.

According to a press release, the decision to keep the name took Audubon Society 12 months and included input from more than 2,300 people from across the their chapters network and beyond—including survey responses from more than 1,700 NAS staff, members, volunteers, donors, chapters, campus chapter members, and partners and more than 600 people across the country with a focus on reaching people of color and younger people. NAS also commissioned historical research that “examined John James Audubon’s life, views, and how they did—and did not—reflect his time.”

The society said that North America had lost three billion birds since 1970. Birds act as early-warning systems about the health of our planet, and they are telling us that birds—and our planet—are in crisis. Based on the critical threats to birds that NAS must urgently address and the need to remain a non-partisan force for conservation, the Board determined that retaining the name would “enable NAS to direct key resources and focus towards enacting the organization’s mission.”

The reality? No matter what else happened in the life of John James Audubon, his legacy and association and name are forever entwined and synonymous with bird conservation. And the removal of that name would not only damage the National Audubon Society, but open the society up to new Audubon groups, as one has to use a name brand to keep it.

Still Called Out History

In the statement, Bell still elected to call Audubon a racist, and announced a new $25 million commitment to fund the expansion of Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging specific work. Part of the commitment is a board committee level “Chief EDIB Officer.”

“We are at a pivotal moment as an organization and as a conservation movement,” said Audubon CEO Elizabeth Gray, in their release. “The urgency of our climate and biodiversity crises compels us to marshal our resources toward the areas of greatest impact for birds and people. This means centering equity, diversity, inclusion, and belonging values into our programmatic work, as well as our internal operations, and implementing our new five-year Strategic Plan. Regardless of the name we use, this organization must and will address the inequalities and injustices that have historically existed within the conservation movement. I am confident that, like birds, the Audubon of tomorrow can be a powerful unifier and force for conservation.”

The National Audubon Society was founded 50 years after his death. Audubon called him a naturalist and illustrator whose work was an “important contribution to the field of ornithology” as well as an “enslaver, whose racism and harmful attitudes toward Black and Indigenous people are now well-understood.” and cited “inequalities that have been inherent in the conservation movement.”